"1920s & 1930s: The LezQueer World before Bars"

My podcast with Sinister Wisdom, Our Dyke Histories has launched! I'm sharing the transcript from the first 1920s-1930s episode with some images to bring it to life even further.

Our Dyke Histories has launched! Huzzah!

A year of interviews, learning to edit the pod, and Our Dyke Histories is up and running. I recently read that if everyone knew what was involved in doing a podcast, and doing it well, they wouldn't do it. True. And I'm say the same for grad school, children, or being alive. In sum: it's worth it.

As an added bonus, I'm going to drop in the transcripts from the issues and give you some of the images (see above). Here's a link for every podcast app. Enjoy!

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Welcome to Our Dyke Histories. I'm your host, Jack Gieseking, historian, geographer, and environmental psychologist. We dive into the past and present of lez, queer, trans, sapphic, and nb communities, decade by decade, in collaboration with multicultural, lesbian literary and art journal, Sinister Wisdom. This season, we're all about dyke bars* with an asterisk, lesbian bars, queer parties, and trans hangouts — the structures that made them necessary, the lives they made possible, and the worlds we made from them.

Our Dyke Histories: Come for the history, stay for the revolution, gossip and desire that built us. 🤌

Lillian Faderman: I'm happy to meet you all and looking forward to this program.

Jack Gieseking: Okay, hot dog.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: We hear so much about the closure of lesbian bars and now recently their revival. But how did they start? Where did they come from and why do we love them?

Welcome to the 1920s and thirties. While parties secretly flourished in the twenties, the first publicly identified lesbian bars won't emerge until the 1930s. Why did they start then and where?

Get ready to go back a century to make sense of so much of the world we have now.

Please note that this episode reads like adult queer life. It contains discussions of sex as well as some discussions of violence that some people may find disturbing, including fascism abuse, murder, the worst parts of Jim Crow, and all the isms and phobias.

As a heads up, this is part one of two about the lez bars, queer parties, and trans hangouts of the '20s and '30s. Because our conversation got so juicy and delicious that we could not stop recording, we have two incredible guests this week.

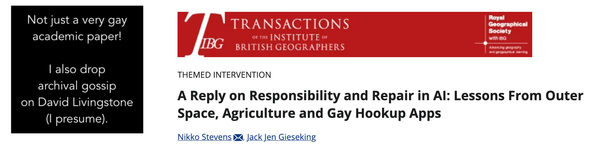

We have two incredible guests this week. First up, one of the queens of L-G-B-T-Q in particularly lesbian history. Of her many books, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in 20th Century America, was passed around college for decades by everydyke, including me. And in 2016, the guardian named that book, one of the Top 10 Books of Radical History.

Lillian Faderman: I am Lillian Faderman and I've been writing, first Lesbian History and more recently LGBTQ plus history, since the mid 1970s. In 1981 I did surpassing the Love of Men, and I've been writing ever since.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Our other esteemed guest is a cultural historian of race, gender, and sexuality in the modern us.

Cookie Woolner: Hello everybody. I'm Cookie Woolner. I published The Famous Lady Lovers: Black Women and Queer Desire Before Stonewall, which focuses on the twenties and thirties. So I'm very excited about the topic today and very excited to be in conversation with you both.

The 1920s Queer Parties before Lez Bars

Jack Gieseking: We should start with this kind of landscape level view. Are there lesbian bars in the 1920s and thirties, and what do they look like? What do they feel like? Are their queer parties? What are they like?

Lillian Faderman: I'll start. There were places where lesbians could go in the 1920s in America. If you were a lesbian and you were in Germany or France. In 1926, there were fabulous bars like Damenklub [00:02:00] Violetta in Germany that started in 26 and in Paris that started in 26.

In the States there were not many public venues that were exclusively lesbian.

There had been places where lesbians and, gay men and people that we would now call trans or--, L-G-B-T-Q wasn't a term then of course. There were semi-public. places where they could go. And we know that through, various autobiographies. I'm thinking for example of Mary Casals' The Stonewall, where she talks about, how she and her lover Juno went to a homosexual resort, and saw both lesbians and gay men together. There was no exclusively lesbian place.

The first exclusively lesbian places I should say, that I know of in the United States-- there were two in Los Angeles on the Sunset Strip, both opened in 1936. One was called Jane Jones Little Club. The other was called Tess's International Cafe. And it had various names through the year. At one point it was called Tess's Continental Club. Oh, and Mona's in San Francisco also opened in 1936. Those were the first exclusively lesbian bars.

So There weren't, exclusively lesbian bars in the 1920s in Los Angeles, but there were house parties and some of them fabulous. Maybe the most fabulous was the silent film star Alla Nazimova's house party. She had a mansion later called the Garden of Allah, and she had these fabulous house parties with Angenous and this swimming [00:04:00] pool.

And the story was that aspiring young actresses would just be so anxious to be invited to those parties. They may or may not have been very sexual like orgies. Some sensationalistic biographers have suggested they were orgies, but that's not necessarily true. But that young Angenous who were invited often believed that it would somehow further their career to make contacts with people like Alla Nazimova.

She was really a fascinating personage. She had her own film company for a while. She was about to do a movie in which she proudly announced that she was going to play a boy. She had a masculine persona, although she was very feminine on the screen, one of the first vamps.

But despite that, eventually she married a gay man. It was clearly a front marriage because, by the 1930s in Hollywood, it was a little dangerous to be suspected of being exclusively lesbian. It was okay, sort of provocative, to be bisexual, but exclusively lesbian was not provocative. It was considered abnormal.

Bisexual was sort of chic, certainly in the twenties and in the thirties as well.

Before that, as far as I could see from my research, lesbians did go out at night to public places, but they were usually places where gay men went and tourists went as well. Rather than an exclusive lesbian place, such as existed later on in the 20th century.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: When Lillian says that bisexual was sort of chic while lesbianism was forbidden, bisexuality was seen as okay because they assumed that women would come back to men. Oof da. Talk about some stellar cis [00:06:00] hetero patriarchy.

You may be wondering what Jane Jones, Mona's, and Tess look like...

I dove deep, and you can definitely find photos of these places online. One of them was actually from Life Magazine: Jane Jones Little Club on the strip. And then there's a wonderful photo of a singing hefty, thick, and delightful butch Jane Jones .

Someone found an actual video from Tess's International Cafe 1950 of the well-known Jimmy Renard, " one of the tall broad shoulder women who wore a tuxes and bow ties with tenor voices."

All of these places with their bar to the side, an area to dance, there's always a stage. There's a really kind of polished, mid 20th century looking microphone. some kind of performance space. All of these places set up a certain definition of what a Dyke bar might or could be.

The Mafia Made Gay Bars

Cookie Woolner: And of course, it's very important to also keep in mind that for much of this period, right from 1920 to 1933, we have prohibition going on. So purchasing alcohol is illegal.

And so, you know, the spaces we now think of as bars-- I mean, Speakeasies were what we had at the time, right?

Somewhere like Harlem there's hundreds and hundreds of speakeasies and, while we , know through a lot of folks work, you know, including of course Lillian, as well as people like Roey Thorpe, that black queer women often prefer to socialize in private right in, in their homes.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: One way to conceptualize what's happening in the 1920s is that we have so many bars emerging for lesbians, for gay men, mostly LGBQ people, right? Really mixed scene. And they're happening at this moment because of prohibition. The mafia would serve anyone who would pay them money. And so this entire infrastructure grows of illegal L-G-B-T-Q, gay, lesbian, trans speakeasies.

And then when they become legal again, the mafia doesn't wanna give up this huge amount of money. They're paying off the police to run these rackets and make more money off of queers . So [00:08:00] that's where these bars come from.

Cookie Woolner: Through, the existence of, of vice records, which were usually mostly being created to track sex work. We found a lot of examples of black queer women gathering together in Harlem Speakeasies. Putting blues song on the jukebox, dancing together in ways that the vice reformer watching found to be very, very shocking and scandalous.

So we do know that they also gathered in speakeasies, even though these were usually mixed spaces in terms of race and gender.

Lillian Faderman: Also that I think one reason there weren't early, exclusively lesbian places was a matter of economics. A bar, any public place, can't make it, if you rely exclusively on a population that doesn't have much income. And I think that was true of probably many lesbians in the 1920s and the 1930s. When women started to be employed more, that was when lesbian bars proliferated.

Cookie Woolner: Plus, there'd been such a stigma until around, I think like the 1910s when we first have kind of the beginning of like heterosexual cabarets, right? Where the assumption was that if a woman was in a place that served alcohol, that meant that she was a sex worker. So oftentimes middle class women aren't gonna feel comfortable going into bar type spaces until later, or they prefer to gather at home as well.

Jack Gieseking: I remember finding the Cafe de bo Arts ladies bar, which was the first bar in the 1910s that women can publicly drink at. There's a great drawing of these women in the, the giant hats and the giant skirts of the period. I don't even know how they got on a stool.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Clearly the women who are able to gather at the cafe de Bo Arts are very dressed up and have the money to do so.

There were working class parties and private gatherings all along, but in the 1910s, we're just imagining and just slightly dipping our toes into publicness. We do get a glimpse of this in the well of loneliness when Radcliffe Hall writes about her fictional character of [00:10:00] Stephen Gordon, a play on herself as an ambulance driver in World War I. There's an actual butch mask in an independent job-- but I'm getting ahead of myself. Let's get back to tea rooms.

Jack Gieseking: And before that, obviously there were tea rooms, right? So, lesbians couldn't gather in public. But Even during prohibition, people are creating what they call tea rooms.

Lillian Faderman: The 1920s there was, in Greenwich Village, for instance, there was Eve's Hangout, which was essentially a tea room, but it was a lesbian place. But alcohol certainly wasn't served openly. People might have brought their own flasks, but uh, it was prohibition. So for the most part, people drank tea in lesbian tea rooms like Eve's Hangout.

Jack Gieseking: Do you think this is why we love tea so much? I wonder It's, you know, it's a cultural pursuit.

Lillian Faderman: I'm a coffee person myself..

What Dykes Could(n’t) Afford

Jack Gieseking: But there's also fragments of histories of bars in Chicago too, like the 1230 club. And one of my favorite things is a place called the Rose Inn or the Rose L Inn.

And the fact that there's three or four ways to spell it and no one can remember.

Lillian Faderman: I think they weren't long lasting for a couple of reasons.

The rose was raided incidentally I know of it, through a newspaper article that described the raid. Um, But they weren't long lasting also because the proprietors couldn't make it on the little bit that women would spend. And that's why, you know, it's always struck me as interesting that even at the height of gay bars, like in the 1950s, there were so many more bars for men than there were for women.

Because many more women were employed obviously in the 1950s than they were in the twenties and thirties, but they still had jobs that weren't as lucrative as jobs that men, even gay men had. And they [00:12:00] just, they couldn't support a huge proliferation of bars.

Jack Gieseking: John D'Emilio's brilliant capitalism and gay identity article about, finally women are employed. They actually have an income. And masses of people are creating early nascent lesbian and gay community and, and the first lesbian gay organizations.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: What I just said about D'Emilio's chapter is a short take by one of the granddaddies of LGBQ history , who wrote that because the so-called sexes had been divided by World War ii, men were sent to the front ; women were left at home. But in that way, so many gay men were forced into small quarters and so many lesbians the same in labor and they get to find one another for the first time.

Also because women again over overgeneralizing and can finally make money, they can rent and afford their own place. They can define their own life. Political economy has so much to do with how we're experiencing this.

If you wanna bring this into the common era, I know we joke about uhauling. I also find it funny, but that's really expensive. Every time we have to find a new place and move around, rents are raising on us .

In fact, when I was mapping all the places ever mentioned in Les queer publications in New York City spanning 25 years, I was shocked to see Bed Bath and Beyond and almost left it off the map. But then I realized that must be where we get our new rugs for the bathroom.

Anyway, it's important to keep this in mind because it's part of the reason we can't afford rent and we can't afford to all be together.

Sex, Racism, and Surveys

Let's go back to a period before all of these significant shifts, and what feeds those changes.

Jack Gieseking: But before that, coming into the 1920s, we have the popular imaginary is this jazz age. There's this sexual revolution, there's bohemians. And at the same times, eugenics is now a global movement. The Great Depression is happening.

How would you talk about how we land in the 1920s?

Cookie Woolner: I tend [00:14:00] to focus on the the tensions of the era, right? We often tend to focus on the ways that it seems like it's more liberatory, a progressive time, you know, politically very conservative still, right? It's still the height of the Jim Crow era. The height of lynchings. in the south. There's still tons of segregation in the north, which of course is gonna affect so much of the different spaces that queer women are hanging out in and finding each other in.

Along with, we have the birth of the birth control movement, but then this connection to eugenics as well. So there's impulses coming together in this conflict to create this new, modern society.

Also just a decade in which everything is speeding up. Like the pace of life is becoming more mechanical.

Lillian Faderman: Cookie is absolutely right. I would also add that, there, there were pockets that were certainly very liberated. The whole image of the flapper, which was not only, uh, an idea in big cities such as New York or Chicago, but spread everywhere eventually. So women were, for a brief period, at any case, more liberated.

There's an interesting book that was published at the end of the decade of the twenties by Katherine Bement Davis called Factors in the Sex Lives of 2,200 Women. And that has always fascinated me so much because she looked at women in the 1920s, and she found that 50% of her sample of the 2,200 women said that they had been sexually attracted to other women. And half of those, about 25% said that they had had sexual relations with other women. And so things were certainly opening up in the 1920s in this flapper era. But publicly, I, I think they weren't as lively for lesbians as they were for [00:16:00] heterosexuals.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Why do we care about this study by Katherine Bement Davis? It's so important for us to take these large surveys because they give us a glimpse of the landscape of who we are. When we've been kept apart, when we can't be in public space together, we don't really know things about one another or how we operate. But More people did research through the 20th century that demonstrated the utter reasonable existence of LGBTQ people.

We can think about the large gender census survey or something smaller but still amazing, like The Testosterone Zine recently released by Rene Yehuda Klein, which was personally helpful to me, and I'm sure some of our listeners contributed to.

The person you've probably heard of, Alfred Kinsey, interviewed over 6,000 women and 5,300 men, and he's where we get the idea that about 10% of the population is gay. We actually have no idea what that number is. But we make those kinds of surveys and give us that kind of information.

Also It's been a long time. Somebody's gotta interview 6,000 people again.

Very Gay Hollywood

Jack Gieseking: That makes total sense. When you said there's different pockets, it's really important to talk about how different places are.

Cookie, your book is about New York. Lillian, you've written a lot about California, especially la. I was wondering if we could talk a little about the differences between San Francisco, New York, and LA and any other cities that come up too.

But how do you see that city as different during this period? What's happening uniquely there?

Lillian Faderman: We have to remember that in the 1920s and even in the thirties, Los Angeles was not a huge city the way New York or uh, Chicago was, it was relatively new. The area of Hollywood had actually been this very quiet, um, little conservative town in effect until the movie industry. And people in the movie industry were not welcomed in West Hollywood, which was [00:18:00] called Sherman, in particular, they were considered, uh, immoral and it was really thought that they would bring all sorts of moral disturbances to what became West Hollywood.

And indeed they did. They.

Jack Gieseking: We hope forever. Yeah.

Lillian Faderman: But I, I think it was people who were attracted to that area of Los Angeles through the movie industry who were really responsible for some of the first gay bars.

And I I should explain that the term gay was an umbrella term for all of us in fact, in, in the early decades of the 20th century. It included not only men, but lesbians and people who now identify as transgender, and certainly people who now identify as queer. And even people who identify as bisexual would be subsumed under gay. It, it was a term that covered the entire community.

So the the first gay bars in Los Angeles, they were in two places actually. There was one in South Central Los Angeles, which was uh, black area, at Dunbar Hotel on Central Avenue. But I shouldn't call it a gay bar, because it attracted not only gay men and lesbians, and certainly people who we would call trans today, but also tourists and straight people. It was essentially a jazz club. But there were performances by both uh, what was called, male impersonators and what was called female impersonators.

Off of Hollywood Boulevard, I should say, there was Jimmy's Backyard and there was the BBB cellar in the area that we now call West Hollywood around the Sunset [00:20:00] Strip.

In the Hollywood area, there were places that really drew in uh, movie crowd people who had come to Los Angeles to work in the new film industry.

Jack Gieseking: And would we find Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn hanging out at these places in--?

Lillian Faderman: You find Kerry Grant and Katherine Hepburn and Marlena Dietrich hanging out at those places!

I have a wonderful story about Marlena Dietrich that when I was doing my interviews for odd Girls and Twilight Lovers, the book came out in 91, so the interviews were mostly in the 1980s. Um, I met a woman who had actually gone to Tess's International Club where Tommy Williams and Jimmy Renar who were what was called in those days, male impersonators -- now, of course we would say trans . They were both entertainers, very tall, handsome people who wore tuxedos, bow ties.

But the story that I was told by this woman was that Tommy Williams, the singer brought Marlena Dietrich into Tess's International Club and sang to her through the evening.

Wow. What I would give to have been there!

Jack Gieseking: Oh,

Lillian Faderman: Would that have that totally fabulous?

Jack Gieseking: That is fabulous.

“Gender Impersonators” in San Francisco

Why I got excited when I was writing and thinking about dyke bars is a more complex system was especially inspired by this period, by the twenties and thirties. And reading, I'm sure another one of our shared favorite books, wide Open Town by Nan Boyd about San Francisco.

I had done research in New York, but it is so wildly different than San Francisco where they're not regulating prohibition, in the same way. It stays wet city. And the political economy of that blew my mind. You're not paying off the mafia who are paying off the police. [00:22:00] You're directly paying off the police. The way I understood it, and please correct me if I'm wrong 'cause it's not my period: The city is surviving, financially in, in large part, on sexualized and racialized tourism. These incredibly racist acts of Chinese people and black people as well. Um, you have so many more spaces forming where gay people in the broad sense of the word are hanging out in the audience of male impersonators, as they're called, female impersonators.

They're assuming that straight people are coming to watch these acts-- And there's an audience of gay people happening. so it's creating a different kind of community than anywhere else in the US because of these large gatherings.

Lillian Faderman: Well, one of the most popular places in San Francisco starting in the 1930s was Finocchios, which was a a place where so-called female impersonators entertained. The audience presumably was mostly straight, but of course there were gay men and lesbians who also went to Pinocchios to meet each other and to see the entertainment.

Pinocchios was still going in the late 1950s where-- and I went there. I was brought there by a gay man to whom I was briefly married in a front marriage, and he took me to Pinocchios. It was really fabulous to observe even the audience in the 1950s, many of them straight, but also of course, many gay men and some lesbians in the audience.

Jack Gieseking: Wow.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: I wanna add a little bit more clarity on the racialization and exoticization of people of color in these spaces by quoting directly from Wide open town, which is the first queer history of San Francisco.

Boyd pays close attention to the history of Finocchios . She writes, [00:24:00] "one night, an impromptu performance by a female. Imer sparked Joseph Pinocchio's interest. As journalist Jess Hamlin notes quote: A well-oiled customer got up and sang in a dazzling style that sounded exactly like Sophie Tucker. The crowd ate it up and Pinocchio saw his future. Female impersonators " were a sensation," joe Finocchio recalls. He went on: everyone came to see the show and to drink. Initially, the show featured a female impersonator paired with a quote, exotic dancer. There were a hula dancer or a young Chinese dancer. In this way, Pinocchios combine gender transgressive and racialized entertainments, establishing a pattern that would continue through the postwar years."

These two elements always went together in this sexual and racial exoticization of tourism.

Lillian Faderman: There was still that kind of mixing, even in the 1950s of tourists being attracted to look at the queers as it were. And queer in those days, I should say, was not a positive term. So the straight people there, it was queer tourism in effect, and lesbian and gay people there.

And of course trans people, which was not a word in the 1950s. Trans people there as well to look at these so-called female impersonators.

Queer Harlem after the Great Migration

Cookie Woolner: so Turning to New York a little bit, I should say first that my focus really has been Harlem. So I I was looking in the 1920s of, um, odd girls before this to refresh myself.

I was glad to feel kind of validated in what I remembered you know, Lillian did talk about how there weren't what we now conceive of as lesbian bars in Greenwich Village at the time.

When I think about white lesbians and feminist in Greenwich Village, the Heterodoxy Club is one of the first groups of people that I of, right? Which is white, middle class, you know, progressive, lefty women who are having meetings, talking about issues like around feminism, lesbianism, sexology, Freud, [00:26:00] free love-- the term for non-monogamy-- anarchism, peace, war. it's kind like an, an intellectual group.

And Of course we do have intellectual gatherings going on in Harlem as well, very short-lived , ephemeral spaces is kind of definitely key for talking about queer women's spaces in general, and especially black queer women's spaces.

We have Alya Walker, the, hes the daughter of, the first female, self-made millionaire, Madam CJ Walker. She opens a literary salon in Harlem called The Dark Tower, which is only open for a year, but is a real kind of key space for Harlem Renaissance artists, white patrons, you know, lovers, friends, people together.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: When we look at Cookie's book, she talks about how the Dark Tower was also known as quote "the Harlem Artist Rendezvous. We don't know whether Aaliyah Walker's love of women can be proved to pull a word from blue's history. But the Dark Tower invited those to register as members and bring friends to enjoy an evening of real informal human association where people may sing dance, play cards, read or simply converse."

Cookie goes on to describe the room as " beautifully decorated and lettered with quotations from the poetry of County Cullen" as well as Langston Hughes.

Now back to Cookie.

Cookie Woolner: And we also know through the amazing, oral history is done by maple Hampton by Joan Nessel, the lesbian Herstory archives. That Maple Hampton attended some very, very sexy parties at Elia Walkers as well, where pretty much everybody was naked. And you know, there's people of all different kind of types of couples together, according to her.

Lillian Faderman: I was lucky enough to interview Mabel Hampton, and she told me that you had to be, she said you had to be cute and well dressed to get into those parties.

Cookie Woolner: That is amazing.

Jack Gieseking: Oh my gosh.

Cookie Woolner: I also just wanna mention another really key aspect of what's going on in history at the time that sets the stage [00:28:00] for queer life in Harlem, which would be the Great Migration, which has not yet been named. The, um, mass migration of Southern African Americans to northern and western cities starting with World War I, plays a key role in reshaping the demographics of northern cities, right? Leading to a lot of what are still kind of called race riots, even though they're really just, you know, racial violence mostly by white men towards, black northerners, black southern migrants.

So we're seeing of course during the Jim Crow era, a lot of racial violence in the north as well. And I'm, I'm a northerner, but I not teach in the South, so I always like to talk about, racial violence in the north. Because we still still tend to have, especially northerners, have these stereotypes around just happening in the south.

Queer Rent Parties Rage On

everything is incredibly segregated in Harlem and the reason that, you know, queer parties known as rent parties become so popular. And actually it's a rent party where Mabel Hampton meets her partner, Lillian, who she's with for over 40 years.

Rent parties are happening because the rent is so high because Harlem is one of the only neighborhoods where black people are able to live. And so their white landlords know that they can jack up the rent as high as they want, and they don't really have any choice in the neighborhood they live in.

And so it's because rent is so insanely high that they're having these rent parties where people are-- are kind. basically it's mutual aid. It's like a great depression form of mutual aid where people are helping to pay the rent. And when you pay admission fee to get in, then there'll be drinks and food and oftentimes entertainment as well.

So the advent of rent parties where women often met was very much because of racism and segregation in the Jim Crow era, in the norms.

Jack Gieseking: And we have those documented in cities like Detroit and different parts of the US South in New York City through at least the 1960 seventies, probably still ongoing. But calling them rent parties and buffet Flats.

Cookie Woolner: They actually have a really interesting history coming out of Pullman porters. So the Pullman train cars, the sleeping train cars, being a Pullman [00:30:00] porter was seen as a really great job for black men, a very kind of middle class job to work on the trains.

Originally Buffet flats were actually created as parties for traveling Pullman Porters, but they just became, by the twenties and thirties, more often private parties in, often women's homes, oftentimes thrown by black women who sometimes were madams, part of the, underground sex economies.

Sometimes they were entertainers or former entertainers. One of my favorite descriptions of what I think actually comes from Detroit and it comes from the, biography about Bessie Smith. She's describing some very wild kind of different types of sex acts, like sex circus types of performances. And they seemed to be very queer spaces.

But I don't think they, always were. It is one of those things where some earlier queer historians say they were always queer spaces. And some people say they were sometimes queer spaces. These aren't the kind of larger, more mainstream clubs, places like the Cotton Club.

All Things Gladys Bentley

Connecting what you were talking to in San Francisco, this practice of slumming, right? Where white people, are going out to clubs to see black and queer performers. Somebody like Gladys Bentley, who of of course we need to talk about, comes to the center stage performing in clubs that are very much part of this kind of slumming world where the performers are black, sometimes the help is black, but the audience is to be white or white passing.

So we're still, again, seeing the racial segregation.

Lillian Faderman: The Gladys Bentley story has interested me, particularly as a sign of changing times in the twenties. She was very much out. She dressed in tuxedos and made a point of her being a lesbian. There was nothing hidden about it. Supposedly she actually married a woman, and it was well known in Harlem that she was married to another woman. Uh, Not recognized by the state, of course, but it was a public [00:32:00] ceremony.

An indication of how times can change: in the 1950s she did an interview for Ebony Magazine, actually called "I Am a Woman again," in which she talked about having hormone treatments to make her a woman and she got married to a man and, whatever part of it is true, we'll never know.

The point is that she felt she had to say that because times had changed so much and it was a huge difference between the fairly open 1920s and the very conservative 1950s.

Jack Gieseking: So that's really hard to hear, but what part of Gladys's journey we don't know.

And Gladys Bentley from all accounts and descriptions was just, and the photos, I mean, everyone Google Gladys Bentley right now listen to her music even in the scratchy records. It's amazing. And see what a cutie, she was like always in a tuxedo, a stud and a half. What a role model.

How to Navigate a 1920s Police Raid

I was thinking about New York City too, we had mentioned Eve's hangout earlier, and Jonathan Ned Katz wrote the Daring Life and dangerous times of Eve Adams. One of the things that I loved about that book was the idea, you had said you could bring a flask, but you could buy a setup. So you could buy your lime and your tonic and you could come in with your gin and a flask. There is this expectation, besides tea, that something else is there.

So How do we imagine like the mafia and prohibition? How scared would you be to go out to have tea or another beverage or be around someone else having alcohol? There's so many speakeasies. How does this work? What does this feel like?

Cookie Woolner: There's a really great description in the biography of brick Top/ Ada Smith. was a figure similar to Josephine Baker. [00:34:00] She was black woman from the US who over to Europe to, to Paris, during prohibition and was very successful there and stayed over there.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: After we recorded this episode, I became a little obsessed with the flaming Red hair and freckled bisexual black woman who may have had an affair with Josephine Baker, AKA Brick top. In 1924, brick Top was in Paris. She hosted Cole Porter and f Scott Fitzgerald. to her parties, and Porter hired her as an entertainer, often to dance the latest dance craze, including the Charleston, the Black bottom, et cetera. The song miss Otis Regrets by Cole Porter was written especially for her. And many other famous people wrote songs for her, including Jengo Reinhardt.

At 28, she sang at the Montmarte Club where she befriended none other than Langston Hughes, who wasn't quite famous yet.

From what I've read about her, she was really into cigars, popular in cafes. She also knew the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Bummer. They turned out to be Nazis.

Her proteges. Are you ready for this? Duke Ellington and Josephine Baker.

Of course, it was tragic that the club she opened in Paris in 1929 would be closed because of World War ii. She left for Mexico City and then returned to Europe where she created a club in Rome, which hosted-- this is amazing-- elizabeth Taylor, Frank Sinatra, and Martin Luther King Jr.

I love bisexual history.

Cookie Woolner: Brick Top Ran clubs and she gave a really great specific description of what it was like when you're in a speakeasy and there's a raid.

She made it sound like it was a pretty regular thing that happened. Oftentimes there would be like a, a bell that would go off ahead of time and people would put the alcohol away. Couples would sometimes have to change who they were dancing with and then often would leave and just know, go back to how you were before.

It seems like it wasn't always necessarily like dangerous, but I'm sure there were other instances where people were concerned about going out. And then also just In terms of queer women going [00:36:00] out, there's some descriptions from Mabel Hampton about women who would prefer wearing one thing on the street and then bringing clothes and changing when they get to the venue that they're trying to go to. If they have to take public transportation, which was often the case.

So I've also read a lot about what women are doing to kind of feel safe you know, as as visibly queer people on the street when they're trying to go out to a nightlife space as well.

Lillian Faderman: In Los Angeles, there were city ordinances against cross dressing, but for decades, it was mostly men who were picked on in the uh, 1920s. There were entertainers who appeared in men's clothes, women entertainers even walking into the bar, walking on the streets. They weren't in trouble for doing that.

Things began to change starting in the 1930s. By the 1950s women were picked up off the street just walking in pants and tailored shirts. But I think that things got increasingly conservative in Los Angeles, beginning, in the 1930s, but reaching the height of it in the 1950s.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: so If you haven't heard of the red lights of the mid 20th Century bars, these likely evolved as a leftover from speakeasies where they flipped a light to tell people the police were coming and get the hell out.

In other words, they're much like the mechanism cookie described about the bell telling people, telling GBQ people had swap partners.

Men dancing with men and women dancing with women would suddenly have to switch partners when the light went on because they were about to be raided. Oh, what a history we have.

Lesbianism beyond Cities

We haven't said it yet, but we need to get to the rural, because most of the US at this period in time is not yet urban and there are no suburbs like we know them today --my opinion? Hotdog -- until post-World War ii. Here we [00:38:00] go.

Jack Gieseking: There's this amazing chapter by Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy about south Dakota lesbianism in the 1920s.

So I wanted to read an excerpt from her interview with a woman named Julia Rubenstein. ' cause it's just hot, everyone.

So this young woman's father, he owns quite a large company. He is considering buying a helicopter.

And so my father announced to me this one weekend we'd be spending the weekend in Rapid City because Amelia Earhart was going to bring a helicopter from Denver up to demonstrate. She represented the helicopter company. So she arrived at the hotel and she and I were assigned to one room.

And we should say that Julia Rubinstein has told Elizabeth Kennedy that absolutely people would just not tell each other that they were lesbians. They would be friends, they would be in a couple going out with other lesbian couples, and no one would acknowledge at all that they were gay, that they were lesbian, homosexual-- inverts as as the word from earlier times, nothing.

So Amelia Erhardt shows up at the hotel:

Of course, I was terribly excited because this was Amelia Erhardt and here I was still in college and she landed at the airport, rapid City. And this very attractive gal got out of the helicopter in a flying suit, soft voice, but it had a timber to it.

And there was a little bit of authority about her. She knew what she was doing. She spoke with authority. I had thoughts immediately when I saw her, but I put them in the back of my head. The conversation was strictly straight.

Anyway, they wind up sharing this room together. Amelia puts her hand on her shoulder. Could she? Would she? And she doesn't! And she still regrets it for the rest of her life.

But this kind of rurality versus urban queerness. How do you see that being different, like across a place like the us? It's such a gigantic country and we're still really rural at this point, right? [00:40:00] We don't have the cities that we have now.

Also, if you've never seen a picture of Amelia Erhardt, please Google another hunk and a half. My Goddess.

Lillian Faderman: There's an astonishing study of women in Salt Lake City, Utah, in the 1920s and thirties, middle class women who had a big circle of lesbian circle of friends. Who of course were very secretive for the outside world, but they had a wonderful social life within the circle.

So I think that was happening all over the country. People were closeted.

In fact for my book, gay la I interviewed several women who were teaching in the 1940s and fifties. One woman in particular who told me this interesting story about how for 10 years she and her partner would play gin rummy every Friday night with a colleague, another woman, and uh, the woman that the colleague lived with.

And they would usually play at the colleague's home, which was a one bedroom apartment. And to get to the bathroom, you had to go through their bedroom. And it was clear that there was just one bed there.

For 10 years, the couples never said a word to each other about how they were lesbian. You did that at great peril.

You had to remain very closeted because if you were wrong, or if they claimed you were wrong, you were in big trouble, you would lose your job.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: I can't amplify enough how profound this is to me forever in a day that the love that dare not speak its name, what being queer used to be called meant not even saying it to your closest friends of decades, or maybe even to your partner or your lovers. It's shattering.

Lillian Faderman: [00:42:00] And so it's not surprising that in smaller towns or in the Midwest or in the South, lesbians were extremely closeted and didn't dare go to public venues as they did. And, in some of the bigger cities.

Conclusion

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Thanks for listening to episode one.

I know, I know. We ended on a bit of a bummer, just like a, a profound mark of closeted, but we could not end on that note.

We'll be back next week with everything, rent, parties, sex and drag, how queerness traveled, how dykes really felt about The Well of Loneliness, Paris salons, and, to my knowledge, the only exclusively lesbian bar guide in the history of the world. Thank you to our amazing guests.

Cookie Woolner is Associate professor of History at the University of Memphis.Her first book, The Famous Lady Lovers: Black Women and Queer Desire Before Stonewall was nominated for the Publishing Triangle's Judy Grand Award for lesbian nonfiction. She's also editor in chief of the forthcoming of The Schlager Anthology of LGBTQ History. Prior to becoming a historian, she was a musician and performer in San Francisco.

Lillian Faderman is Professor Emerita and a pioneering LGBTQ historian who's been writing about lesbian and LGBTQ history since the 1970s. The Guardian dubbed her "the mother of lesbian history." Her award-winning books include Surpassing the Love of Men, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers, The Gay Revolution and Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death.

Thanks for tuning into Our Dyke Histories in collaboration with sinister wisdom. Connect with us on Instagram and Facebook at @OurDykeHistories. Follow and support me Jack Gieseking via my newsletter, Queer Geographies. It's packed with everything we could fit into this podcast. Our dyke histories is run by a queer dike and mighty team.

ODH is hosted, edited, and produced by Jack ing co-produced and co-edited by Kate Waldo and co-edited by Mel Whitesell. Our social media manager is Audrey Wilkinson, and our fabulous interns include Michaela Hayes, Sid Guntharp, Paige LeMay, Sophie McClain, and Sarah Parsons. Our theme song "Like Honey" was graciously gifted to us from Kit Orion at kitorion.com.

We're forever grateful to our co-producer Julie Enzser and the entire team at Sinister Wisdom. Publishing since 1976, Sinister Wisdom recognizes the power of language to reflect diverse multicultural lesbian experiences and to enhance our ability to develop critical judgment as lesbians evaluating our community and our world/

We share Our Dyke Histories so we know more about who we are, how we were, and what we fight to never forget.

Lez keep doing it, y'all.