"Queer Pulp, Dark Bars & the Police State, 1940s-1960s"

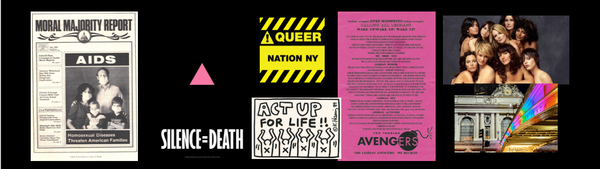

Along with a lush photo spread of some queer highlights, awfulness, and delicious everyday life from the 1940s-1960s, enjoy a deep dive into NYC queer history with Joan Nestle, Hugh Ryan, and Alix Genter.

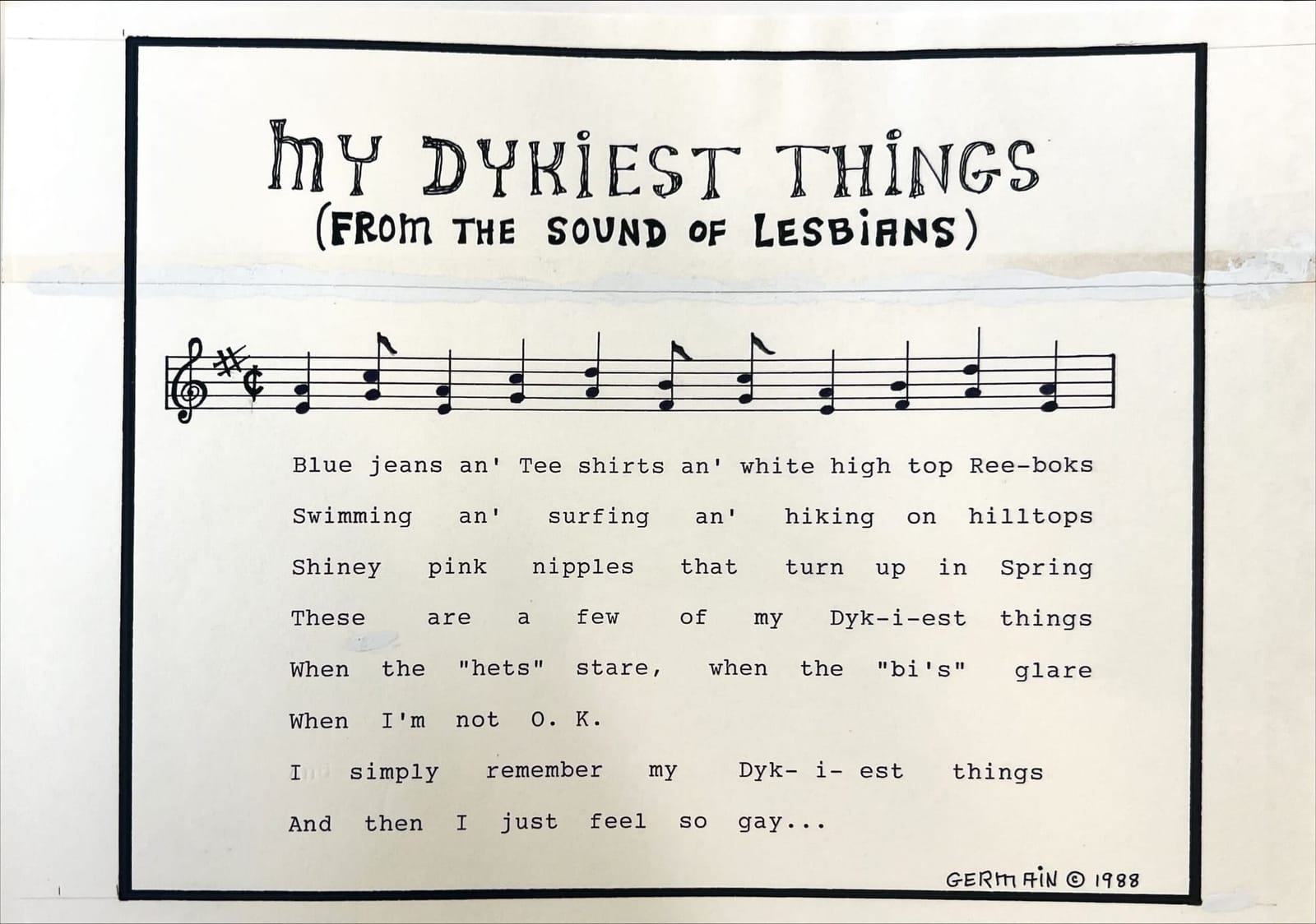

I had to slightly pause QG posts–and we'll even be skipping next week in Our Dyke Histories, sigh–as pneumonia is Just The Worst, y'all. But I'm slowly back it and excited to regale you with all things queer, trans, mapping, dataviz, academic, writing, job search, and geography geography geography. IOW and in the season of sing-a-longs, lez cue up "These Are a Few of My Favorite Things," particularly "My Dykiest Things" version (and very lez forward of the '80s, y'all, so brace) shared by my old friend Margaret Galvan in the June L. Mazer Archives. Thanks, Mags! What's below? More to enjoy, including:

- a lush photo series of the lezbiqueertranssapphic 1940s-1960s,

- a TL;DR transcript below on behalf of hell-yeah accessibility and the I'd-rather-read-it types (which evidently includes the therapist community of Northampton, MA),

- and embedded episodes too and of course.

In our 1940s-1960s episode of Our Dyke Histories, I got to chat with three powerhouse queer historians: Joan Nestle, Hugh Ryan, and Alix Genter. Swoon. From Greenwich Village’s lesbian bar circuits to the Women’s House of Detention and the surprising queer history of Coney Island, the episode uncovers the joy, danger, and erotic electricity that defined mid-century queer life. Featuring the first half of Joan Nestle’s final interview(!), this conversation offers an emotional, intergenerational look at the bars, books, femmes, butches, and bodies that made public lesbian life possible.

Introductions

Welcome to Our Dyke Histories. I'm your host, Jack Gieseking, historian, geographer, and environmental psychologist. We dive into the past and present of lez, bi, queer, trans, sapphic, nb communities, decade by decade in collaboration with multicultural, lesbian, literary and art journal, Sinister Wisdom. This season, we're all about dyke bars* with an asterisk: lesbian bars, queer parties, and trans hangouts– the structures that made them necessary, the lives they made possible, and the worlds we made from them.

Our Dyke Histories come for the history, stay for the revolution, gossip and desire that built us.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Today we journey into the 1940s through the 1960s, from the oppressive moral rigidity of McCarthyism and the most asinine crud of people like Roy Cohn, to the first sparks of rebellion that would spark movements and the delicious, spicy drama of queer pulp. Together we unpack the radical role of desire, bars, prisons, house parties, the mafia and the state, as well as intergenerational lezbiqueertransness in conversation shaping queer lives of the past, present, and surely the future.

Two things to tell you in advance. For those of you who know Joan Nestle, the originator, co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, she told us right before we started talking that this would be her last interview. So I hope you enjoy it as much as I did. It's immensely special as she is.

In order for you to get some full on Joan, [00:01:00] especially given that this was her last interview, I made a special episode we'll release next week of those long stories that Joan gifted us in this chat.

Also, I did not mean to recruit three New York City queer historians-- oof da, said me the New York City queer historian. I am conscious of the fact that queers talk way too much about New York City, but I do hope it gives us a chance to dig really deep into the city in the period preceding Stonewall and to talk about our resistance through places and people alongside and beyond just Stonewall.

Let's keep unpacking that.

Along with the brilliant historians, Hugh Ryan and Alix Genter, we start with a fabulous Joan Nestle:

Joan Nestle: Thank you all for asking me to be part of this. I found it a very emotional moment. I'm 84. I came out into these bars that are now the subject of historical examination, so I wanna dedicate this to communities first. I'm a [00:02:00] writer. I'm co-founder of the Lesbian History Archives. I have moved from the clandestine, dangerous, life-giving bars through the streets of the Women's House of Detention, or the "country club" as it was called. And I'm a survivor. I want to dedicate my time here to that community. It was my Sea Colony bar community, it was the working-class community of many genders and in the iron will of desire to be where the touch you wanted was. I decided that we created a new gender, the gender of desire.

Hugh Ryan: My name is Hugh Ryan. I'm a historian based in New York City, mostly working on queer history in the U.S. And it's a real pleasure and honor to be here today connecting with Joan, with you, with Alix, with sinister wisdom. I'm just so excited.

Alix Genter: I'm Alix Genter, based outside Philadelphia. I'm a historian of butch- femme culture in the mid- 20th century.

Where Our Bodies Entered Public Life

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Welcome, everyone! The 1940s through the 1960s were a time of enormous transformation shaped by World War II, post- war conformity. In the US we see the solidifying of a white, cis-heteronormative ideal in the 1950s, only to have it challenged by waves of resistance in the sixties.

How do we even describe the landscape of lesbian bars, queer parties, and trans hangouts during the 1940s, '50s, and '60s?

Joan kicks us off--

Joan Nestle: I put stories of the body as a starting, because I wanna emphasize the transformative power that made us take on, for me, 1950s' McCarthy America and how it transformed however we, we thought what a woman was, what a [00:04:00] man was.

It was a rich darkness. And we created, because of the power of desire. We focus so much on bars and, yes, that's where became our public. We became the public face of our bodies. That's where our bodies entered public life.

We were creating spaces for desire to be enacted. The bars were one of those spaces.

The body, when it is possessed by this knowledge, that you had to take on really the whole society around you.

If you come from a working-class background, you've seen the police state in many ways in your own intimate life.

There were wonders, necessitated wonders by the horrors of the state. Desire can create not only its own gender, but its own country, its [00:05:00] own powers of resistance.

I talk about darkness because that's where we were regulated in a way.

And I'll shut up.

Alix Genter: No, don't.

Jack Gieseking: Don't ever shut up.

Hugh Ryan: No!

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: My goddesses, why would Joan Nestle ever stop being heard? Please, Athena, let that never happen.

Some of the Worst Gays

When we talk about HUAC, that is the House un-American Activities Committee led by Joseph McCarthy in the late '40s into the '50s alleging that hundreds of people in the government were communists, and that eventually he extended his list to say that many of them were homosexual. This led to these targeted attacks to from government, Hollywood – some of who were gay themselves.

Closely working with McCarthy was someone else you should know about named Roy Cohn. He is surely one of the worst gays of history. Roy Cohn is the person who specifically targeted and prosecuted the Rosenbergs. He was a deep libertarian, a fearmonger -- who you may know as the sort of fictionalized villain in [00:06:00] Angels in America-- and a cruel lawyer who was eventually disbarred, but not before he mentored a young man named Donald Trump. We can see where he got it from.

Alix Genter: When I was thinking about, what I wanted to research for my project, Joan's writings really inspired me. That desire was so potent, the desire and the danger together, and the excitement that those generate together, really grabbed my attention and sucked me in -- besides just being super hot.

But the spaces, just filled with that desire. They were filled with smoke and women and just desire. That is how I think about them and how I try to write about them so that other people can feel what I never really did.

I admire the women from this time period so much for seeking that out, which was not just going against [00:07:00] heteronormative society. But it was going against ideologies of womanhood that were very strong. Seeking out sexual partners, going out at night, un chaperoned or, just wandering around, and seeking non-marital sex, seeking multiple, fulfilling relationships throughout a life, not a lifelong monogamous marriage or commitment. These were things that women did not do, and the fact that they chose to do it, knowing the risks, and followed that desire, is just very profound to me.

Hugh Ryan: A lot of my work in this particular time period, the forties, fifties, and sixties, is like the dark mirror. Not that it's not connected to bars, but so much of the history I look at in this time is the institutional side.

On Being Labelled Crazy and Criminal

Institutional in a very negative sense of queer, lesbian, dyke spaces, women who have been imprisoned, women who have been [00:08:00] sentenced to mental institutions, which becomes more and more popular after the 1950s when homosexuality is added to the DSM. Spaces like the military, which are voluntary but of a certain kind of conscriptive nature.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: All too many of you are likely familiar with the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-- we're now in version five. But in the 1950s, absolutely included homosexuality and what was then called cross-dressing and other aspects of transness in its many forms.

It's not until 1973 homosexuality is removed as a mental disorder. And this was a huge effect on our psychology: as we're talking from the forties to sixties. People think that they're mentally ill for being gay, for being trans.

In fact, it wasn't until 2013 that what was called gender identity disorder, this anti-trans medical [00:09:00] diagnosis, was switched to gender dysphoria, having the anxiety, stress, depression induced by being trans and a cisgender world.

I remember the day that it changed. I was actually teaching. I went into my students and I said, “did you know that now I can wear these clothes as a butch, trans masc presenting person that I am, and no one's gonna put me in a mental institution?”

And it's the first day in my life where that happened. And I remember the wow in their faces, and I remember the wow in my heart. Whew.

Now back to Hugh Ryan.

Hugh Ryan: These are incredible spaces for queer women to meet each other, for trans folks. Throughout this period. Prisons are incredibly important, in this history and are connected to the bars.

They're where people end up after being at the bars; they're where people socialize outside the bars. But we rarely think about them as social spaces.

My work moves in and out of the bars and connects with the bars, and connects as you [00:10:00] were saying, Joan, with that feeling of being an outcast together and being outside of that mainstream light of institutions , marriage.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: When we say bar, again: what do we even mean? It's a physical space, sure. But it seems like something more in the way we're talking, in the way that lezbiqueertrans, and gay men talk too. It's more: sometimes a sanctuary, a battleground, a home. Even in the 1950s, bars are affording this sense of connection. We need to always keep unpacking that.

Because it wasn't just that there were these bars in Greenwich Village, there were a large number of them. Actually, there were more than a dozen in this period in Greenwich Village alone. But you had to get between them. There are travel stories : we also have to think about how you even get from bar to bar. Because they're connected to one another as queer bodies go between them, go between their homes and work, take public transportation, walk or roll down the street, and go to other queer spaces as well.

And I have some of those in my next episode with [00:11:00] just Joan Nestle. It's pretty amazing.

Mabel Hampton, out Black lesbian from the 1910s till she passed in her eighties, was a longtime friend of Joan's and her collection is central to the Lesbian Herstory Archives. In one of her oral history interviews with Joan for the LHA-- i'll post the links to listen to the all on queergeographies.com-- Hampton says: “you know, in the thirties and into the forties, people wouldn't wear slacks to walk down the street, they would take a cab together with their short hair”. Cabs are very expensive and it's not just that people are going from parties, going between parties and their homes and work and bars.

There are other places they're going to, and that's what brings us to the Women's House of Detention.

Hugh Ryan: I wrote about the Women's House of Detention, which was a combination jail and prison located in Greenwich Village from 1932 to 1974. Even before that, there was a [00:12:00] prison connected to the Women's Court from 1910 to about 1940. There was a prison that was not specifically for women, but was connected to this house of detention, and it was an epicenter for queer culture.

I think one of the things we don't think about is still to this day, 40% of people in incarcerated in women's prisons identify as LGBTQ. And at the time the Women's House of Detention was open, it was probably around 75%.

I found this research largely through following the footsteps of Joan and a few other writers like Audre Lorde, who really have highlighted the role that the prison played in lesbian communities of these time periods, thirties, forties, fifties and sixties.

And the research that I did into it showed me how much more broadly this affected the Village, the nature of New York City, our understanding of queerness, and our understanding of how, queer people socialize.

Joan Nestle: And real estate in New York. How played in the capitalist sense [00:13:00] of respectability.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Joan is exactly right. As we explore these histories, it's impossible to ignore how geography, political economy, and power intersect with queer life-- even define it, and we define it back too. We think of the formation of gayborhoods, or what we call gay ghettos as being something of the 1970s and eighties, and then we think about the gentrification of gays out of cities, or the gentrification of gays in cities in the 1990s and thereafter. Nowadays, corporations like BlackRock, Blackstone, Invitation Homes, among many others, are buying up properties and raising rents, and resale values on us all.

But there are other processes working here too, like gentrification way back in the 1950s. If you need to understand what happened in the fifties, just think about suburbs, these white, middle class, cis het, ableist, norming spaces that blew their way through forests and wetlands, forcing us into individual [00:14:00] so-called family units . As the suburbs soar full of whiteness, who is left in cities? If cis and straightness are moving to the suburbs-- or we think they are on the surface-- the city has become the places of blackness, of queerness, of poverty, of deviance. Of those people who are left behind, of those people who are radical and don't wanna be part of this normalization and this construction of a certain version of America.

In the midst of all that queer people were gathering, they were finding each other in bars, house parties, parks, prisons, beaches, street corners.

Joan Nestle: But I want to say on that walk to the bar, I passed the Women's House of D, as we called it. And it took me a long time to get lesbian feminist movement to cast their eyes to that building. So it was exile.

I wrote a poem [00:15:00] about the garden because how most contemporary-- your contemporaries-- know it as a garden. They tore that prison down and replaced it with a garden. To me, that's what we're talking about: we can write books about the bars, but society was invested in destroying that community and that time.

There's Miss Hampton's writing about prison and how, for her, it was a place where she found the embrace of women -- complexities within complexities.

Like that Women's House of D, they can plant all the fucking flowers they want there. But they will never drown out both the pain and the touch– and the riven families, lesbian families. Those late, summer nights when usually it was butches calling up to femmes who had been arrested for shoplifting and sex work. [00:16:00] And they will never drown that out.

As long as I am alive and as long as any of us can remember. You have to carry that on. That's what I wanna say for anyone who does listen to this eventually.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: There are constellations of lezbiqueertransness over the ages, and where do we even start our history? We often talk about mid- 20th century queer history because that's when we have a visible queer public.

Gay Greenwich Village Revolutions before Stonewall

The revolution of the 1960s has a long history deeply attached to Greenwich Village, particularly because it's the location of the Stonewall Bar, which is the location of the 1969 Stonewall Riot. A riot by BIPOC queer, trans working-class, poor sex worker, hustler, disabled people who had no other choice but to revolt who were fed up.

I am another homotrans who loves Stonewall, but I do think we often get too fixated on it. We get so hyperfocused on this one event and, and expect the myth and the monument [00:17:00] of it to carry us into the future when we are so much more diverse, broad, complicated, and equally amazing in so many ways.

The queer revolution started way before Stonewall in these bars and parties, in the Women's House of Detention, in so many other places like cafes, restaurants, and even our homes. And if we don't recognize that we risk the chance of our revolutions yet to come.

Hugh Ryan has also written that: “about 500 feet separated the prison, the women's House of detention and the bar, the Stonewall Bar, the incarcerated, and the liberated, the forgotten, and the immortalized 500 feet between those who quote birthed the modern gay rights movement and those, the movement has ignored some of those incarcerated had windows that looked down Christopher Street. They would've heard the sirens and the screams smelled the burning trash and flock to see what was happening. What a wonderful way to think so [00:18:00] differently, more critically, and to reclaim more of our history around Stonewall. Thanks, Hugh.

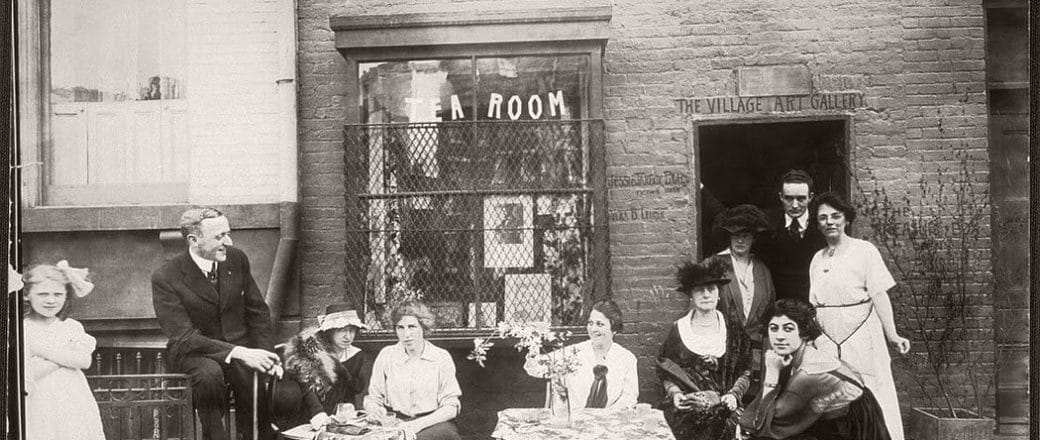

Joan Nestle: For me, this whole history goes back to the '20s. In the bohemian, in the Harlem Renaissance, the bars in New York were sites of interracial couples where they could feel safe. So interracial reality and queerness were joined in this kind of bohemian places to be in all of this.

Hugh Ryan: I think it's so important that you make those connections, and I know we're here to talk about the forties, fifties, and sixties, but I agree that this goes right back to the 1920s, the 19 teens and I would in fact argue that the only reason Greenwich Village is known as a Bohemian neighborhood is the opening of the women's court.

The women's court was built specifically to be a forced feminization process on women who were deemed not properly, white, Victorian, feminine. Women who were too masculine, women who were too [00:19:00] sexual, women who were disobedient.

And the court was set up as a form of entertainment. They literally had raked seating and advertised with flyers saying, “You'll always have a good seat. Everyone is welcome”. The goal of the court was to show off the evils of prostitution.

In that period when the court opens in 1907, up until then, Greenwich Village is known as Old Greenwich, the quaintest and most backward part of New York City. And only after the court opens in 19 10, '11, '12, does it start to develop this reputation for being a bohemian epicenter.

And the descriptions of the bohemians are almost exactly the same as the descriptions of the women being arrested and sent to the court. It's women who wear pants, who drink, who smoke, who have sex, who talk back to their parents. The line between Bohemian women and incarcerated women basically came down to, did you have money? Whiteness? Access to [00:20:00] respectability? But without that court, Greenwich Village would not be Greenwich Village as we know it today.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: The history of queer trans life is intimately implicated in and defined by prisons. Abolition movements have shown us new ways of thinking and action. They've come out of amazing organizers including, of course and always, Angela Y. Davis-- in part through Davis's conversations with the brilliant trans black femme queen, Miss Major, who recently passed away, but whose words and ideas stay with us forever.

If you're not sure how to be part of that abolition movement, you can at least go on to Pink and Black and get yourself a queer trans imprisoned penpal and send them some cheer.

Creating Joy amongst Tragedy

And the radical desire of embodiment is why Joan keeps bringing us back to our bodies...

Joan Nestle: I lay the groundwork of flesh, of the lived body, before it becomes a textual page. So my contribution to this. [00:21:00] It is a living voice, a living body of that time.

Because uptown there's a whole thriving, black, lesbian- queer community that's been going on forever. So yes, hard times. But communities were creating all the time acts of resistance because of that iron will of desire, for self- presentation, cloaked in love, cloaked in valuing-- and remember we're talking HUAC American. Subversion is in the air. It didn't take very much to be labeled a traitor to all Americans.

Alix Genter: To go back to the prison, and creating community spaces under extreme oppression, within the House of D. I found that women really, if not created full- blown [00:22:00] community, there were practices that enabled romance and friendship. Women would look out for guards for their friends so they could have sex in somebody's bed. They would send kites to each other, little notes.

And if somebody had a birthday, I think this was Flory Fisher's memoir about her time, her various stints in the House of Detention-- but somebody's birthday, they put up some toilet brush as a limbo pole, and everybody's limboing underneath. Whoever had money at the commissary bought some snacks and someone did like a titillating dance. That kind of joy or attempts at joy under such repressive and awful circumstances is really a testament to, not just queer women, all marginalized people.

Hugh Ryan: Yeah, those expressions of desire and creations of community are some of my favorite parts in doing this research. Everyone's always [00:23:00] “is it sad researching the 1950s? Is it sad talking about the 1930s?” And I'm like, “sure there are sad parts, but it's actually wonderful because I feel like I'm seeing things more clearly.”

There was this great story in the late sixties. This researcher, this straight woman, comes into the women's house of detention and she wants to study what she's calling the “play family,” which is women who form these relationships as apprenticeships, getting ready for heterosexuality somewhere in the nebulous future. Like she has this whole idea of what's happening that is obviously not what she discovers. In fact what she's looking at are lesbian relationships and extended prison relationships, prison families that are established while being incarcerated and have roots on the outside.

She starts off noticing and telling her supervisor that “there is an unusual number of Black, Jewish women in the prison”. And her supervisor's like, “what are you talking about? “she's

saying,

“I'm seeing all these Black women wearing stars of David.

She finally goes to talk to the women. And it turns out there's only two kinds of jewelry allowed in the prison: you can wear a Star of David or you could wear a cross. And so for Black femmes, the stars of David from their Jewish girlfriends did not have a religious connotation. But were instead this really high- fashion item, the only one you could have in the prison. So they called themselves the Sammy Davis Jr. Club and the prison had no idea what they were seeing.

Jack Gieseking: Oh my goodness.

Alix Genter: I love it.

That is amazing.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: It is amazing to hear this joy and reclamation in a prison. Hugh is about to say “this isn't a romantic history”. Something that Joan herself taught him and called him and others out on. But we do fall into that trap and we need to be careful.

What We Do/n't Romanticize

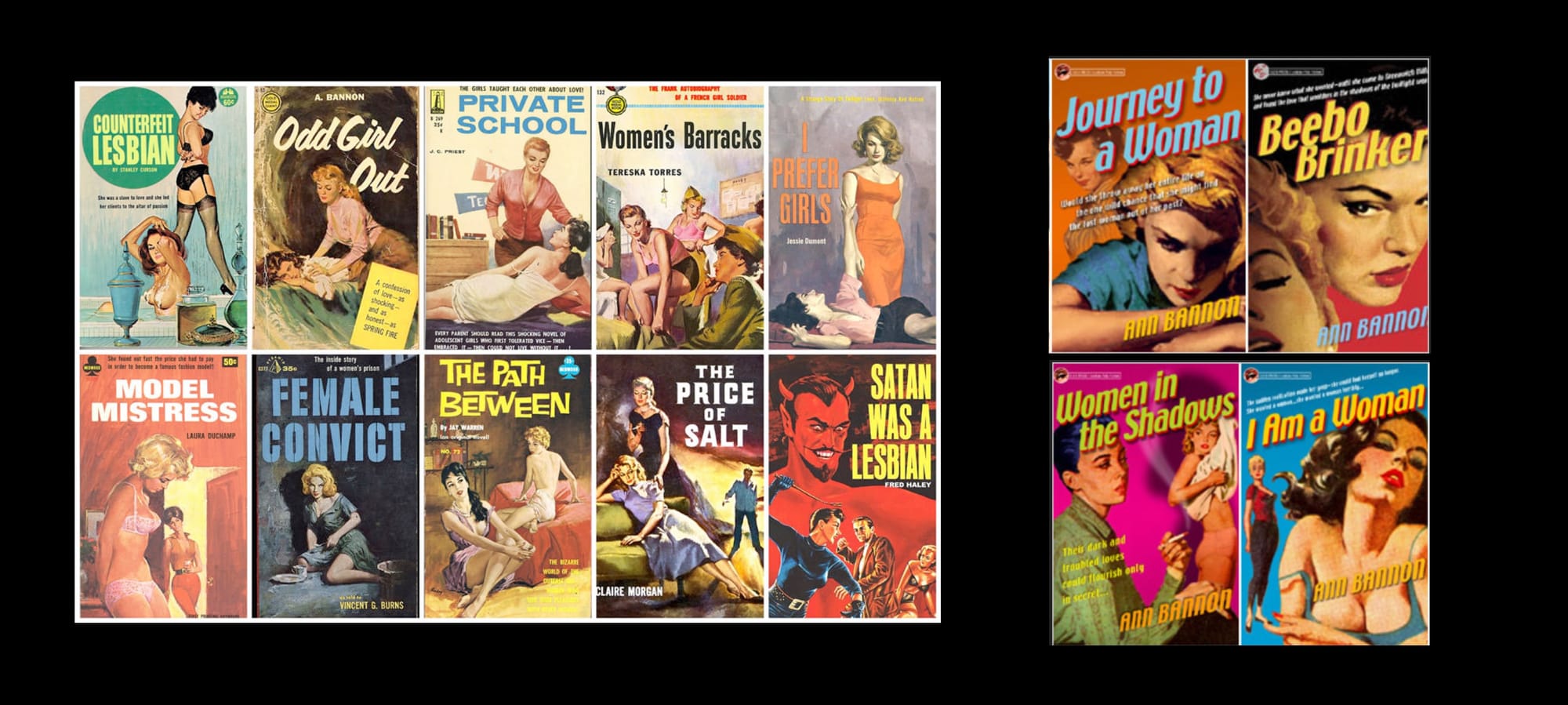

One of the ways that I think the 1950s gets exceptionally romanticized is through the queer pulp. These dime store paperbacks literally they cost a dime, and they had these tawdry covers, very sultry, deep [00:25:00] looks. Everyone's kind of half dressed. And this is how a lot of people were learning about queerness at the time. About lesbianism, about gayness.

One of the most famous collections of lesbian pulp and all queer pulp is none other than the Beebo Brinker Chronicles , written between 1957 and 1962 by Anne Bannon, who located Bebo's life in her world, which was the Greenwich Village lesbian world.

Our own Alix Genter for her research had interviewed both Bannon and Joan Nestle and she writes:

“Central to Bannon's depiction of lesbian experience was Butch Femme. As indeed as Bannon asserts about the primary couple in her books, "Laura was feminine in the traditional way. Her defenses, her fear of emotional entanglement quickly melted under the laser of Beebo's sexual focus. And on her side, Beebo was intrigued with Laura's beguiling femaleness. I knew of no other way to write about them." Later, “Alix writes, Joan Nestle a femme carousing. Yes, our Joan in this episode. “a Femme carousing “[00:26:00] “Greenwich Village Bars. At the time Bannon was writing, joan felt that Bannon's books depicted, quote, "A world I could recognize and sex that I could respond to." Unlike The Well of Loneliness-- [“ “which we talked about in depth in our 1920s “and 30s “episode as being quite a bummer], which was Radcliffe Hall's classic 1928 lesbian novel that was “too upper class and European for Joan. Instead, she said that Bannon's books felt accurate and familiar. “She added, I never stood a chance with Stephen--” “but Beebo? Well, maybe.”

Ah, thank you for that, Alix.

It also seems that queer pulp is always having a renaissance, a bit like lesbian bars.

And so we walk the fine line between knowing something shouldn't be romanticized. It does become sensationalized. There is desire, there is survival, and how do we make new worlds?

Joan Nestle: This kind of intergenerational conversation should be done more because there's such, I don't know, enrichments and [00:27:00] differences. I wanna keep commemorating. That's my impulse. Your impulses are to discover.

How you put it into your historical narratives, that I give over to you.

You'll have your time when you will commemorate those who didn't survive the time of which you are writing, but also share your flesh.

Alix Genter: I so appreciate that Joan. When I did this research, the women that I was talking to and whose voices I was reading or gleaning from between the lines were so important to me.

Continuing to talk intergenerationally is one of the most wonderful gifts that someone younger can do, to continue speaking to older generations and learning. And that was a huge part of my historical research, and probably

Hugh Ryan: i, I was just gonna say that I have to [00:28:00] agree. Not only the importance of the intergenerational information, but the actual conversations. Very early in my career, Joan, you actually said to me during an interview, you stopped me and said, “I hear this wonder in your voice, and I'm afraid you're romanticizing this too much”. “These were working- class women using the skills they had to build lives for themselves. This isn't a romantic history, even though it has romance to it. “ “And from the distance of history, it may feel that way. “

You have been so generous with that kind of guidance throughout decades. I really value , not just giving me information about this bar was there, I went here, this woman, this was her name. But yeah, the perspective of now looking back, that's something that can only come through actual conversation between generations.

Joan Nestle: There are many different kinds of romance, but if romance means a glory of impossible joy, then this is the [00:29:00] highest romance of all: which is the creation of life and respect for desire. when all else has been taken away. You see what I'm saying?

That's why these conversations are so important. That they're transformative in how we think about life, and what we're willing to sacrifice.

The Mafia's Control and Reach

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: This episode's talking a lot about Greenwich Village, but I don't wanna leave out other places. Probably an obvious one is San Francisco. San Francisco wasn't controlled by the mafia. Its reach didn't go all the way across the coast, which means actually it's police directly taking bribes from bar owners and profiting from queer life in that way.

And the reason there are so many queer bars and different kinds of queerness and a different kind of openness in San Francisco is because it's thriving on racial and sexual tourism.

Bars like Finnochio's and Mona's that were founded in the 1930s are [00:30:00] surviving off of people like the fantastic José Sarria, this phenomenal operatic drag queen who proclaimed “gay is good”! When Sariya held the room, he not only got the straights to make fun of themselves, but he also got the queers to feel like they were in community.

In the 1960s, Sarria would found the Imperial Queens and Kings, which is still the longest running queer organization in the United States. He was the first openly gay person to ever run for office. His life arc is extraordinary.

But since the mafia ruled the East coast, what's now the Rust Belt and most of the Midwest, that was an entirely different monster to deal with. Along with the police.

Joan Nestle: I wanna say the mafia protected us. It's more complicated. It always is. Bruno who stood at the door, would let the straight tourists in so they could sit at those tables and watch– and I wanna use another word we haven't used : “freak”. We were [00:31:00] “freaks”. That was the heritage I came out of. That's what the doctors told my mother in the 1950s. She thought I was a lesbian. The doctor said, “that's like saying she has cancer”. So that's the horror this was in respectable places.

"I thought of myself as a freak"

We were considered, and I, I thought of myself as a freak. And that again, to me is genderless. It's a whole other world, of all the things we think we know, but we don't when you are a freak.

Alix Genter: This idea of being a freak really speaks to one of the reasons these spaces were so significant and that people sought them out.

That is why a sampling of license plates in the village in the sixties You get stuff from Massachusetts, from New Jersey, from Connecticut, from further away, because people needed to be there.

Despite the risk, despite sneaking out of their parents' houses, despite having to change in the bathroom-- and this wonderful [00:32:00] story about slicking back her Dutch boy- girl hair with stale beers, so she could be a butch in the bar. “A page boy girl hair into a lovely duck's ass with stale beer from a hip flask. “

But, the destination wasn't just to dance and have fun and to express your desire, although those were reasons too. But if you feel like a freak out in the world– akin to sentenced with something akin to cancer– knowing that other people are there like you, and that people are in the same boat or enjoying themselves or loving each other. Or just getting to sit there and smoke a cigarette with someone with a similar kind of life.

Where People Loved Themselves

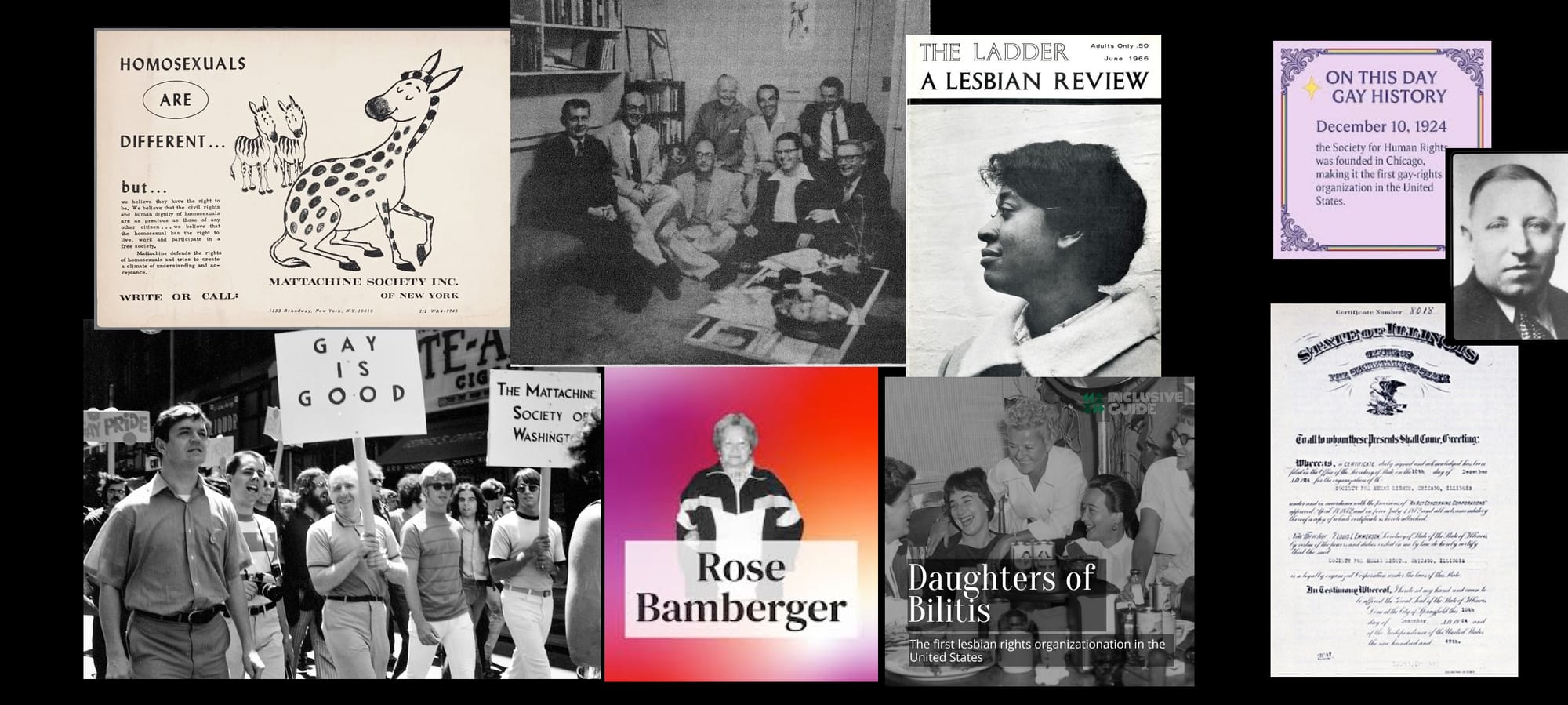

Hugh Ryan: This is an essential part of, of the history that's gotten a little bit, in the mainstream confused, and especially in this period, the fifties, right? All of these Daughters of Bilitis and Mattachine Society and organized groups are springing up, and they're seen as “this bastion of gay pride. “You know, “The first people who said, “[00:33:00] “We are not freaks. “

But you look at them and you read their histories, and what you read over and over again is Harry Hay saying, “I went to the bars. “ “In the bars for the first time. I met people who loved themselves “ “and that enabled me to see a world beyond this”.

Those people, the people who first had that thought, were the ones who were treated like freaks. But who made these spaces, like you were saying, Joan, marvelous on the inside.

And that ability to have that space, where things were beautiful and wonderful, and where you could love yourself and each other, and find the importance of touch.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: I had always heard that the Daughters of Bilitis were founded in response to the Mattachine Society who only let women be secretaries in their organization. Mattachine was founded by communists, but included primarily white gay men, and many were libertarian among them. In fact, it was the libertarians who said we should organize for gay rights. The communists among them were against that. I know that's a hard pill to swallow. It still gives me the wiggins.

The Daughters of [00:34:00] Bilitis were founded by Rosalie Rose Bamberger, a Filipino factory worker who wanted a place to dance with her girlfriend, who of course was named Rose. And she went up hanging out with people like Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin.

There was a sensibility of not wanting to be part of what was known as Bar Dyke culture, this working-class culture that Joan Nestle really found a home and family among. Having a separate place to dance that wasn't either defined by butch- fem working-class politics, controlled by the mafia or police.

But very soon, the Daughters of Bilitis became more of a white, middle- class women's organization that completely rejected the bars and the people in them. But! Thanks to them we do have the first national lesbian publication, “The Ladder”. That wouldn't have existed if someone hadn't been a secretary and secretly mimeographed at work.

But these organizations can fall into the trap of [00:35:00] respectability politics.

Hugh Ryan: And, Alix, like you were saying: then from that one bar to blocks of bars all over, a network of them– those people and places precede the organized gay rights movement and are in fact necessary for it to come.

Where Gay History Comes from: Buffalo

Joan Nestle: Okay. I just have to, I have to mention, um, the work of Liz Kennedy and Madeline Davis in Boots “of Leather, Slippers of Gold.” And I wanna mention all the pioneering lesbian and queer archiving groups gay history groups of San Francisco. We were all in this because our bodies had been touched by this movement .

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: As lesbian history goes, we probably know the most about lesbian bars in the forties, fifties, and sixties in one city. It's not New York. It's not San Francisco. Wait for it. It's Buffalo.

The first chapter of “Boots of Leather” that Joan just referenced is titled, "I Couldn't [00:36:00] Wait to Get Back to that Bar." And the main argument of the book is that bars and parties and other gathering spaces are what they call “prepolitical”. Butches and femmes at the time were seen as anti-political, because as working-class people, they were poor and their survival dependent on keeping their head down, they were already pushing the limits in their gender and sexual being. While there wasn't a so-called movement yet in the 1950s, rather they were laying the groundwork for a more formal social movement. In other words, we were always political because we were politicized.

It's funny, but most people don't realize that Stone Butch Blues is being written about Buffalo at the same time. I mean, Buffalo Dyke history, and I've said this in another episode, but the reason we have so many secure, loud, strong voices from places like the Rust Belt, is because there are union jobs. Some butches and some women can get union [00:37:00] jobs. There's different kinds of labor and possibility.

Joan Nestle: We were all in this because our bodies had been touched by this movement, this iron will of desire. The bars were also a place where we compared our wounds physically and psychologically, where we gave each other important information of how to survive this calamity. Or when the landlord decided to throw you out or where we shared resources.

To be sitting with you all, who have written books and will write books and tell the stories and find the stories. The story that is green with life will be more powerful-- and you'll see, it will outlive the horrors.

I'm gonna say something stupid if I haven't already, because I'm speaking on pure emotion now. Thank [00:38:00] you for listening.

Hugh Ryan: None of it is stupid.

Jack Gieseking: None of it was stupid. It's so good!

Audre Lorde Was a Bar Dyke, Too

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Speaking of the antithesis of stupid and the kernel of all things, brilliant it's time to talk about one of the most major sources for writings about New York City lesbian bars in the 1950s. You'll never guess, but it's that kween of kweens, the Black lesbian feminist poet and essayist. Yes, it's the author of "The Master's Tools Cannot Dismantle the Master's House." It is the fabulous Audre Lorde.

It's important to say at that lesbian bars in the '40s, '50s, and '60s are very much predominantly white spaces. There are definitely Black, brown, Asian, Latinx, Indigenous people within them. The owners are very conscious of keeping the police away, and so they're targeting a white market. And it is whiteness that cloaks, provides protection to lesbian bars, to gay bars as much as the mafia or any other organization at the time.

Jack Gieseking: I did go get the quote from “Zami”, which is from Audre Lorde in the bars. “We met women with whom we would've had no other “[00:39:00] “contact had. We not all been gay.”

Joan Nestle: But Audre also wrote, and I can see her so clearly-- again, I had the honor of knowing her in her body-- that it was in these bars. It was the only time she saw interracial relationships in the lesbian, community was in these bars or in America, in her experience.

In different communities, there are different traditions. House parties were essential in the African American, queer- lesbian community. To a surviving the depression, which is the joke is, as Ms.. Hampton would say:” what do you mean a depression? We are never making money. “These things that get delineated as a national time, they're not experienced in the same way. A catastrophe is always a catastrophe. Racism is always a catastrophe and what it does to the ability to live.

People played as well as endured.

Hugh Ryan: It's, it's [00:40:00] funny, Jack, I was thinking of a different Audre Lorde quote . And this is the one that I returned to for the exact same reasons, but, uh, a slightly different quote: “lesbians were probably the only black and white women in New York City in the fifties who were making any attempt to communicate with each other. We learned lessons from each other, the values of which were not lessened by what we did not learn.” And I love that, that making of space for both in the same sentence.

Joan Nestle: Yes. And there were things that looked like bars, that looked like parties. There were gatherings of friends. Yeah, it's a physical space, but it's other things as well. It's a sharing of resources. When you do this history, you find breaks in the wall of racism.

Black Power Meets Gay Liberation

Hugh Ryan: There's this similar thing that happens in the sixties, jumping our conversation around in time endlessly. There's this great talk between, I think Afeni Shakur and Lumumba Shakur, they're talking about the experiences of being [00:41:00] incarcerated. And how for women being incarcerated in the sixties brought them closer between sexuality and race.

Black women who were straight met queer women who were black and white, queer women who were white, met black women who were straight and queer, and it brought them closer because the prisons, again, were very queer. And they then took those relationships out into the bars and tried to find spaces where they could meet up. Lumumba says, in men's prisons,” It's the exact opposite. We are told by the guards, if you don't kill that guy, it means you're a faggot. And so we have to institutionalize homophobia to protect us.”

The guards protect the homosexuals in women's prisons . They were seen as being kept in special wings, and that was them being allied with the state. They have this nuanced conversation about how the spaces in which you are allowed to socialize by the state helped to define the different relationships that black women in the Panther party and black men in the Panther Party [00:42:00] had with queer people.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Hugh just mentioned Afeni Shakur, a major leader in the Black Panthers, mother of Tupac who was a brilliant thinker in his own right. Shakur was an incredibly important voice in the history of black liberation and gay liberation, in part because she was incarcerated at the Women's House of Detention. It's while she's there that she starts to realize how much these two movements have in common. And it's Afeni Shakur who pushes Huey Newton make a public statement on behalf of the Black Panthers supporting the gay and lesbian movement.

This was a sea change in the 1960s' revolutionary movements.

In the same way, Sylvia Rivera, a Latinx trans woman and major activist and organizer who, with Marsha P. Johnson, would start Street Transvestites Action Revolutionary (STAR). Rivera was Venezuelan and Puerto Rican, and it was her activism that made inroads with the Young Lords, the revolutionary Puerto Rican activist group .

You can only imagine how the white [00:43:00] middle class capitalist, patriarchal, heteronormative society did not like all of us hanging out together. It is when we are in coalition that we are most fierce and our most powerful.

Now let's get back to Hugh.

Hugh Ryan: And I think that It's interesting to see the ways in which, as you were saying Joan, what space we are able to make for ourselves creates these relationships between different kinds of outcasts – until the state steps in and says, “no, you kill that kind of outcast or else.”

Racism and Classism in Dyke Bars

Alix Genter: There were opportunities for interracial interaction. But you know, this idea that white lesbians were welcoming or not racist to black women. There were segregated spaces and a lot of that segregation was by choice. A lot of Black women writing, including Audre Lorde in some cases, writing about this time, didn't feel great in village bars.

They knew that they could go [00:44:00] there-- I forget the exact quote: “I knew that a white woman would say, that's a shame, that someone said something racist to you, but she wouldn't stand up for me in that moment.”

So there was this completely separate house party circuit that started in Harlem and moved around with the people who left Harlem and moved to the Lower East Side, moved to Brooklyn. and then there was a house party circuit there.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: What Alix says is so well put. Lesbian bars and queer parties, they're microcosms of American life itself. They're full of contradiction and joy as much as they're full of racism, classism, ableism, and resistance and resilience. They are never perfect havens, but they are what some of us have had and will have in the future.

Alix Genter: I always really enjoyed comparing how Audre Lorde, again, has a pretty damning, description of a, a primarily white [00:45:00] House party where it was boring. There was music, but it wasn't for dancing. The food was bland and there wasn't enough of it. Everyone was talking politely.

Then she goes to these Black lesbian parties where it's a lot of food, a lot of good dancing, a lot of liquor and a lot more fun seemingly.

And it just is interesting because in my research beyond Audre Lorde, of course, white women had parties, but were more comfortable in bars, and bars existed, at least in New York City and other places.

White women had parties that were more for friend groups, birthdays, Halloween, new Year's or whatever, not the institution of house parties that Black women had in Harlem and other places.

Hugh Ryan: It was something that you said, Alix, about the soft racism that Audre Lorde is talking about where the woman says, “Oh, I feel bad for you, but they're not gonna stand up for you. “

There's almost a modern variation [00:46:00] on it that's happening right now. When people are trying to do this sort of historical work on this very period and on these bars and on these rent parties specifically. I talk to younger researchers who wanna do this kind of work and they throw their hands up. They say, ,” of course I wanna write about, black women in the fifties, but the records just aren't there, there's just not this history.”

And they might, Joan, know your work with Ms. Hampton. But when I talk about the kind of records they're looking for, they immediately say, “I'm looking at the bars, at Daughters of Bilitis,” these spaces that we already know are white. And of course you're not gonna find the records that way.

Starting in the 1950s in New York and in a lot of places around the country, public housing had their own police forces and started to have these rules around why you could be thrown out of your housing, which included having been hospitalized in a mental institution, having been arrested, having parties that were too loud.

And those records actually can help us to [00:47:00] find these socializing spaces because again, the state punishes all of us, right?

There are ways into this history that we have only just begun to scratch the surface on, but it requires us looking at our own racism in the current time, which I think is very hard to do.

We can see the racism in the past, but we can't see the ways in which we replicate it in our own research by following some of those same paths. And that's why Joan, your work is so important and Alex, your work is so important. And Jack, yours. It's like looking at race, gender, sexuality, and geography and how those things interact and how we can both see the ways they're entangled and disentangle them.

Fist Fights and Other Lez Bar Violence

Joan Nestle: Just one other, just, and this ties in also with not romanticizing things, but I've heard when I would speak to middle class lesbians later in life and they'd say, “I couldn't get through the door. “ “There was so much violence.”

I mean, maybe it's my, my own background 'cause there was violence, there [00:48:00] were fights. There was violence, answering violence. The police were violent when they came in for their payoffs and when. So yeah, you had to be tough. And that's another, this is the wonder I think of a femme self. When I say it's, it's beyond gender, that desire. You became tough. I saw a fist thrown.

Hugh Ryan: Part of the history that always occurs to me is the reason that those places show up in our history in that way is that's where the police went. It's not necessarily like we chose to fight at Stonewall. The police knew we'd be there and they came for us there.

Joan Nestle: Exactly. So yes, we were on the map of the state.

Hugh Ryan: And , like you said, the bars were connected to the mafia. The mafia was also against the police. It doesn't mean the mafia were for the queers, but there was a complicated relationship there. And so when the police come for the mafia, they also end up coming for the queers because they're entangled. And so I often think that our [00:49:00] bar histories, like you said, Jack, so much more complicated.

Proximity & Possibility

Jack Gieseking: Alex's dissertation actually starts off by saying, were, if you stood in this certain corner, there was no way you couldn't go-- how many streets was it without hitting a lesbian bar?

Alix Genter: You could walk a few blocks in any direction and hit a lesbian bar.

Jack Gieseking: And there's this great map, and if you go online, we'll have it, if Alex says yes to sharing it– yay.

Alix Genter: I was gonna say something about how that map I made has tons of bars on it and I didn't particularly care that much about finding out when exactly they were in operation.

Because to me, and others too, the bar scene itself was the more permanent institution. That was why people went to Greenwich Village. You could walk a couple blocks and come upon some kind of bar. Those were the days.

"But moving on to sex parties...," etc.

But moving on to sex parties, I just wanna point out that bars were really sexy spaces too. I had fun, listening to stories from older [00:50:00] women about their times, dancing on the dance floor, dancing very purposefully.

One story was someone would come in with a sock, you know, stuffed in her pants and she would dance, and routinely have orgasms throughout the night on the dance floor with this sock in her pants, dancing with the femmes.

Jack Gieseking: Good for her. Good for them.

Alix Genter: And people who didn't have anywhere to go. I mean, that's the spot. The spot was subversive anyway. Go ahead, have sex there!

Hugh Ryan: And I think also when you look at subversive spaces that we don't code as “queer” in any way, particularly when you go back historically into the fifties and earlier. Places like Coney Island's Bump and Grind shows or strip clubs today, tons of women working them are queer. Tons of women have these lives that are connected through these bars that we don't think of as queer spaces because some are actually heterosexually designed.

In the 1950s, there was a queer woman out at Coney Island who like opened her own bars, her own [00:51:00] restaurants. She was a burlesque dancer. She fought Robert Moses. She hired other queer women. Her existence is so caught up with being “for the male gaze”, quote unquote, that she's never looked at as a queer figure.

Joan Nestle: There's pictures of Ms. Hampton. One of her first, uh, how she earned money was dancing in an all black, dance group on Coney Island. And there's pictures. Because people had to work. So they had to find jobs and where can freaks have jobs, you know?

Jack Gieseking: Hugh Ryan's other book when Brooklyn was queer, which covers a lot about Coney Island and it's delicious.

Hugh Ryan: I do love Coney Island.

And I think if we look at these spaces, we're gonna find more kinds of queer socialization in spaces that are bars. They're not dyke bars, but they're full of dykes.

Jack Gieseking: I have to say, we should all be so lucky to be full of dykes, like a bar space or otherwise.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: Honestly, who doesn't love Coney Island? If you're in New York City, you can hop on the F train that goes past the LGBT Center, [00:52:00] Henrietta's and Cubbyhole, Ginger's and Park Slope, the old lesbian neighborhood, those cool, lesbian leaning neighborhoods of Queens-- and you can also go all the way out to South Brooklyn to Coney Island.

It's still weird, it's still wild, and it is beautifully queer. May we all be lucky enough to be as full of Dykes as Coney Island was in its heyday, a literal and metaphorical edge of New York where freaks, artists, and queers made space together.

Conclusion & Credits

Jack Gieseking: I just wanna thank you all and, tell you, you're all fantastic.

This has been a wonderful evening and a wonderful ride. . Thank you. This is awesome.

Alix Genter: Thank you so much fun.

Joan Nestle: Thank you for allowing me as part of your work to go into the future.

Hugh Ryan: I see that the exact opposite direction. Thank you for allowing me the grace to take on part of your legacy and follow in your footsteps.

Alix Genter: Yes, definitely. You inspired my work from the very beginning and [00:53:00] just a fierce femme icon and mentor, so thank you. This was so fulfilling though. Thank you.

To find validation as a very feminine presenting queer person and have a label, have an identity all of a sudden, “Ooh, fem. Okay, I'll take it.”

Jack Gieseking: You in college, I was like, oh, I'm sexy. I'm sexy across time. I had no idea. Butches were hot. To read something where you were, I was beautiful. I had no idea.

Joan Nestle: You are all beautiful. yes,

And we are fierce. We've had to be fierce femmes.

Jack Gieseking: Lucky us.

Jack Gieseking - Narrator: I know, I know that many of you listening are saying, I wanna hear more from Mama Joan. I get it. I feel that, and that's why there is an entire episode next week of all Joan Nestle.

I'm sorry I had to excerpt him from here, but I wanted you to get the incredible dynamic conversation that we felt between Hugh, Alix, Joan, and myself. It's [00:54:00] amazing to be in conversation with these brilliant people. Come back next week and enjoy more of all things Nestle.

Joan Nestle is a Lambda Award-winning writer and editor, as well as founder of the Lesbian Archives. She's edited nine books, written three, most famously “A Restricted Country”, and most recently, from our own Sinister Wisdom, “A Sturdy Yes of a People”.

Hugh Ryan is a writer, historian, and curator. With Peppermint, he hosts the book club and podcast, queer History 101. His books include “The” “Women's House of” “Detention: a Queer History of a Forgotten Prison”, as well as “When Brooklyn was Queer.”

Alix Genter is a writer and editor who wrote the startlingly juicy and lush dissertation “Risking Everything for that Touch”, which examines lesbian culture in New York City from the end of World War II, into the emergence of the Women's Liberation Movement.

Thanks for tuning into Our Dyke Histories in collaboration with Sinister Wisdom.

Follow, support, and connect with me Jack Gieseking via my newsletter at ourdykehistories.com. And connect with us on Instagram and Facebook at @ourdykehistories. All this is where we pack everything we could fit into this podcast!

Our Dyke Histories is run by a queer, dykey, and mighty team.

ODH is hosted, edited, and produced by Jack Gieseking, co-produced and co-edited by Cade Waldo, co-edited by Mel Whitesell.

Our social media manager is Audrey Wilkinson, and our fabulous interns include Michaela Hayes, Sid Guntharp, Paige LeMay, Sophie McClain, and Sarah Parsons.

Our theme song “Like Honey,” was graciously gifted to us from Kit Orion who you can find at https://www.kitorion.com/.

We're forever grateful to Julie Enzer, director of Sinister Wisdom. Publishing since 1976, Sinister Wisdom recognizes the power of language to reflect diverse, multicultural lesbian experiences, and to enhance our ability to develop critical judgment as lesbians evaluating our community and our world/

We share Our Dyke Histories so we know more about who we are, how we were and yet could be, and who and what we fight to never forget.

Lez keep doing it, y'all.

**

Join Our Community

Want to be part of our community? We'd love to have you. 😏 Come comment, connect, and get your gayme on!

- Newsletter to your inbox: Jack's Queer Geographies newsletter with detailed takes on each episode, & more about lezbiqueertrans spaces across time

- Instagram for more dyke visuals and stories @ourdykehistories

- Read and follow our co-producer and collaborator, Sinister Wisdom

- Email us questions and comments at ourdykehistories AT gmail DOT com